Settlements > Nimrud

Nimrud

Background

The Assyrian city of Nimrud, known in Arabic as النمرود was founded during the Middle Assyrian Kingdom by Shalmaneser I who ruled between 1274 BC and 1245 BC. Despite it being a city of cultural and religious significance it was not made the capital until later rule under Ashur-nasir-pal II. Its original name in cuneiform is trnaslated to be Levekh according to Henry Rawlinson in 1850.

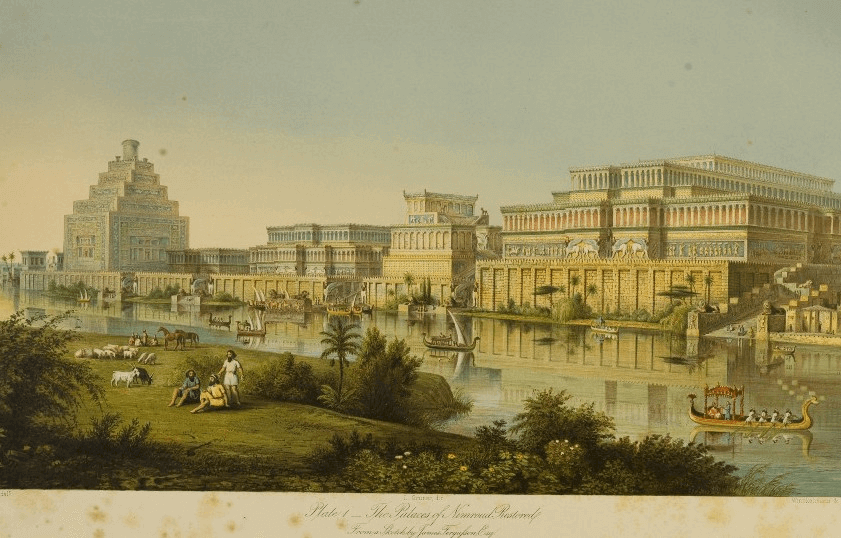

The Palaces at Nimrud Restored - Austen Henry Layard & James Fergusson (1853)

Between the years of 1250 BC and 610 BC which corresponds pretty much with the duration of the Middle Kingdom the city of Nimrud was one of the major Assyrian cities and covered over 360 hectares or 290 acres. Under the reign of Ashur-nasir-pal II (883–859 BC) the capital was moved from Ashur where it had been since 2,500 BC to Nimrud. During his reign he built a massive palace along with temples and the city had a population of over 100,000 people.

By the Dark Ages of 11th and 10th centuries of the Middle Kingdom the city of Nimrud had fallen into a deep state of blight and disrepair due to a major stagnation within the empire.A grand opening ceremony with festivities and an opulent banquet in 879 BC is described in an inscribed stele discovered during archeological excavations. The city of king Ashurnasirpal II housed perhaps as many as 100,000 inhabitants[citation needed], and contained botanic gardens and a zoo. His son, Shalmaneser III (858–824 BC), built the monument known as the Great Ziggurat, and an associated temple.

Ashur-nasir-pal II

Ashur-nasir-pal II was the king of Assyria between 883 BC and 859 BC and was responsible for putting Nimrud on the map as the capital of the Middle Assyrian Kingdom. He conscripted thousands of workers to construct an 8km (5mi) wall that surrounded the city and his massive palace that was adorned with beautiful luxuries from the known world.

There were many inscriptions carved into limestone including one that said: "The palace of cedar, cypress, juniper, boxwood, mulberry, pistachio wood, and tamarisk, for my royal dwelling and for my lordly pleasure for all time, I founded therein. Beasts of the mountains and of the seas, of white limestone and alabaster I fashioned and set them up on its gates."The inscriptions also described plunder stored at the palace: "Silver, gold, lead, copper and iron, the spoil of my hand from the lands which I had brought under my sway, in great quantities I took and placed therein." The inscriptions also described great feasts he had to celebrate his conquests.However his victims were horrified by his conquests. The text also said: "Many of the captives I have taken and burned in a fire. Many I took alive; from some I cut off their hands to the wrists, from others I cut off their noses, ears and fingers; I put out the eyes of many of the soldiers.I burned their young men, women and children to death." About a conquest in another vanquished city he wrote: "I flayed the nobles as many as rebelled; and [I] spread their skins out on the piles." These shock tactics brought success in 877 BC, when after a march to the Mediterranean he announced "I cleaned my weapons in the deep sea and performed sheep-offerings to the gods."[13]Shalmaneser III

When Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) took over rule from Ashurnasirpal he continued much of his fathers policies in relation to military campaigns and public works projects. In addition to waging war for 31 years out of his 35 he built a massive palace that was double the size of his fathers and expanded over an area of 5 hectares (12 acres) and contained more than two hundred separate rooms.

He was successful in defeating the civilization of Aram along with some Caananite and Phoenician states at the Orontes River. An inscription of the battle recorded the following scene;

I slew 14,000 of their warriors with the sword. Like Adad, I rained destruction on them. I scattered their corpses far and wide, (and) covered the face of the desolate plain with their widespreading armies. With (my) weapons I made their blood to flow down the valleys of the land. The plain was too small for their bodies to fall; the wide countryside was used to bury them. With their corpses I spanned the Arantu (Orontes) as with a bridge.

In 828 BC his own son revolted against his rule and was backed by twenty-seven other Assyrian cities including the previous capital of Ashur and Nineveh. The conflict would wage for many years after Shalmaneser III's death until 821 BC and would continue into the reign of Shamshi-Adad V (822–811 BC).

Legacy

Nimrud remained the capital of the Assyrian Empire during the reigns of Shamshi-Adad V (822–811 BC), Adad-nirari III (810–782 BC), Queen Semiramis (810–806 BC), Adad-nirari III (806–782 BC), Shalmaneser IV (782–773 BC), Ashur-dan III (772–755 BC), Ashur-nirari V (754–746 BC), Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (726–723 BC). Tiglath-Pileser III in particular, conducted major building works in the city, as well as introducing Eastern Aramaic as the lingua franca of the empire, whose dialects still endure among the Christian Assyrians of the region today.However, in 706 BC Sargon II (722–705 BC) moved the capital of the empire to Dur Sharrukin, and after his death, Sennacherib (705–681 BC) moved it to Nineveh. It remained a major city and a royal residence until the city was largely destroyed during the fall of the Assyrian Empire at the hands of an alliance of former subject peoples, including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians (between 616 BC and 605 BC).The Nineveh Province in which the ruins of Nimrud lie, is still the major center of Iraq's indigenous Assyrian population (now exclusively Eastern Aramaic-speaking Christians) to this day.Nimrod

Many historians such as Julian Jaynes believe that the figure of Nimrod mentioned in the Bible and whose name provided the inspiration behind the Arabic name of Nimrud for the site is based on real Assyrian kings and their exploits. There is some contention and debate as to the true identity with some beliving it is Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1207 BC) with others beliving it is based on the Assyrian god of Ninurta who was a major god worshiped at the city of Nimrud.

It is believed that the city of Nimrud was also the Biblical city of Calah mentioned in Genesis 10, also known as Kalhu or Kalakh and in Hebrew as כלח and in Greek as χαλαχ.

Archaeological Excavations

Between 1845 and 1879 modern archaeological excavations began at the site of Nimrud and have provided us with a wealth of knowledge about the city. Excavations were resumed again in 1949 and many artifacts were distrbuted throuhgout many of the museums throuhgout the world including Iraq, Britain and the United States of America.Archaeological excavations at the site began in 1845, and were conducted at intervals between then and 1879, and then from 1949 onwards. Many important pieces were discovered, with most being moved to museums in Iraq and abroad. In 2013 the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council established the "Nimrud Project" in order to identify and record the history of the world's collection of artefacts from Nimrud,[3] distributed amongst at least 76 museums worldwide (including 36 in the United States and 13 in the United Kingdom).[4]Archeologists believe that the city was given the name Nimrud in modern times after the Biblical Nimrod, a legendary hunting hero.[5][6]